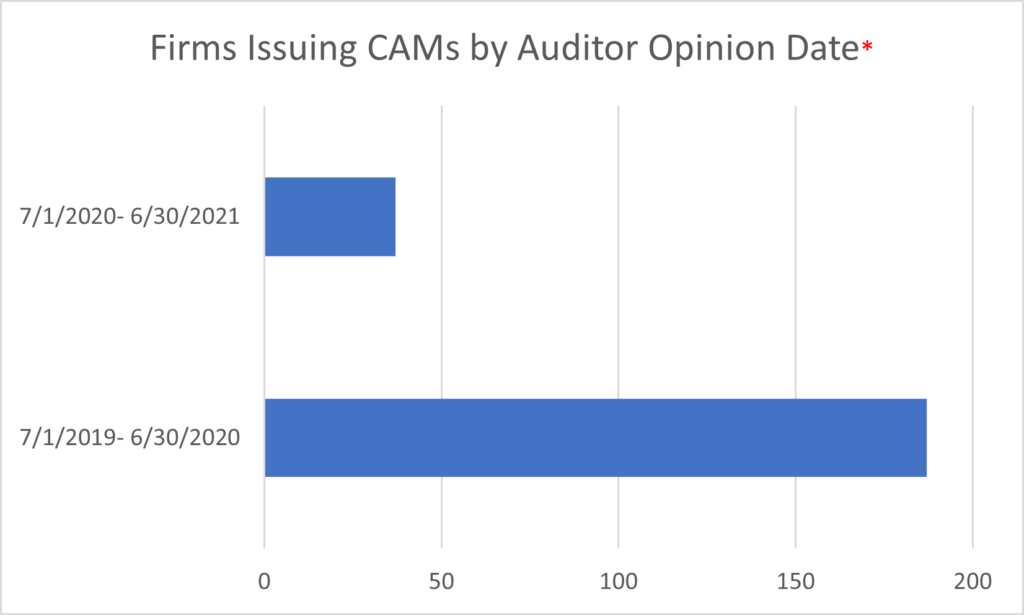

What auditors learned from two years of CAM implementations

When the PCAOB released Auditing Standard 3101: The Auditor’s Report on an Audit of Financial Statements When the Auditor Expresses an Unqualified Opinion in 2017, it was said the inclusion of critical audit matters (CAMs) in the auditor’s report was the most significant change to the audit report in more than 70 years. While this is true, the first two years of CAMs implementation has gone by without much incident. With the majority of public companies now subject to this requirement, it’s a good time to reflect on the impact of CAMs. What has the auditor community learned? How have investors responded? And what can we expect to see going forward?

To best understand why CAMs are important, we must first define the term. According to the PCAOB, a CAM is “any matter arising from the audit of the financial statements that was communicated or required to be communicated to the audit committee and that (1) relates to accounts or disclosures that are material to the financial statement, and (2) involved especially challenging, subjective, or complex auditor judgment.” The PCAOB adopted these changes to inform investors and other financial statement users about significant matters in the audit and how they were addressed.

(Data furnished by Audit Analytics)

Lessons learned

With two rounds of implementation behind us, it’s time to reflect on what we’ve learned so far. As discussed above, critical audit matters are included in the independent auditor’s report in order to bring greater insights to investors and other users of the financial statements regarding the matters that were especially challenging, subjective or required complex auditor judgment. On the surface that might sound like a simple ask: to identify areas within an audit that meet one or more of these criteria and then explain to a user what made the matter especially challenging, subjective or complex, and how you (the auditor) responded to that matter. As auditors have worked to implement this PCAOB standard, it has become clear that this process requires significant professional judgment, a deep understanding of AS 3101 and a significant amount of effort to determine how to explain complex and challenging matters in plain English in a way that is meaningful to the users of the financial statements. Here are three important things we learned from our experience over the past two years:

1. The importance of drilling down: First, we learned that to clearly identify and describe a CAM, we must drill down. Financial statements are a high-level snapshot of the financial position and activity of a company for a given year — they provide some level of detail at the financial statement line item level, but if you think only at that level—you may come to one set of conclusions. To identify and describe a CAM, we must look further to individual accounts and disclosures, and then often to components within those accounts or disclosures. In doing so, we may find different issues that are challenging, subjective or complex. Consider an example of an entity that has goodwill in multiple reporting units, some of which have fair value significantly in excess of carrying value and some of which have limited or no fair value in excess of carrying value. Within each of these reporting units there may be different aspects that are more challenging, subjective or complex. We found that we really need to explore areas at a more granular level in order to enable the auditor to create well-written CAMs.

2. How to avoid a “boilerplate” CAM: We also learned that it is possible to differentiate year over year. Although the standard mandates that CAMs should provide unique and relevant insight about the audit to each client in each year, some auditors were concerned this would be challenging, considering they are often auditing the same areas each year with similar risk characteristics, and that CAMs may become “boilerplate” over time and therefore lose their value. Once the process actually began, it became clear that even for the most common CAM areas, including goodwill impairment, income taxes and revenues, the CAMs actually are different, even in subsequent years. In fact, we’ve learned that if you apply lesson 1 above, this is easier than you might initially think. Having looked at several hundred CAMs on goodwill, it is fascinating to see how different each one is. This is because there is audit variability from company to company and audit to audit. Even where there are similar accounts or disclosures, there are different judgments, types of business and organizational structures. The more granular you are able to get in your assessment process, the easier it is to find differences.

3. Remember the audience: Finally, while the standard allows for several ways to describe how the CAM was addressed in the audit, most CAMs include a description of the procedures that were performed by the auditor to address these matters. There are a variety of factors to be considered as the auditor is drafting this section of the CAM. First, auditors perform a variety of risk assessments, tests of controls (in certain scenarios) and other substantive procedures in performing an audit. Not all of those procedures will be directly responsive to the identified CAM. At this point the auditor applies judgment in determining which procedures out of the full body of work they performed in a given area are directly responsive to the CAM and then describe those procedures in a way that is easy to understand by the users of the financial statements. We, as auditors, have learned that writing about what we do in plain English is difficult. Auditors write in “auditor speak.” Auditors are used to describing the procedures performed using technical jargon, shorthand and commonly used audit terms that are not necessarily easy for the users of the financial statements to understand or interpret. In addition, given the nature of CAMs, these procedures are often complex and challenging, which can make writing a clear description of them even more challenging.

Describing what we mean in terms that are meant for the educated investor is an unexpected and time-consuming aspect of writing a CAM. In fact, it tends to take as much as 50 percent of the time spent on the CAM process overall. This will likely decrease over time as we become more accustomed to describing audit matters in this way. Industry jargon adds another layer of complexity. Take an insurance CAM, for instance. On top of assessing the ability to understand everyday auditing terms, we must determine if people outside the specific industry know the meaning of the jargon we use. For every CAM we write, we must look at whether we need to convert the language into words that are generally known so users of financial statements understand what is being said. We want it to be meaningful and useful to the people who rely on the information we provide.

Investor reaction

We are also seeking to ascertain what this change means for the investor community. While we understand that not all investors are using CAMs in the way they were envisioned, large, sophisticated investor groups appear to be paying attention. A CAM may not tell a different story from that which management discloses, but it does provide information from a different perspective. Investors now have the opportunity to gain additional insights from audit opinions, not just from management disclosures. We’re giving them the opportunity to see “how the sausage is made.” Investors have told us that CAMs are helpful as a window into the big areas auditors are particularly focused on.

In my view, CAMs have improved financial reporting. They give the audit committee and management a different lens to review these matters. When management sees our draft CAMs, they have the opportunity to take a fresh look at previous disclosures and then potentially enhance those disclosures. This has been an unanticipated impact of CAMs, one that management and audit committees appear to welcome.

The road ahead

We have seen approximately 1.7 CAMs per financial statement among large accelerated filers in year one and 1.6 per financial statement among all companies to which CAMs apply in year two. I think it is likely that the number of CAMs will continue to grow, based on the increasing complexity we see in both financial reporting and the economy, and as we get better at applying lesson one discussed above on our engagements. We may also see an increase in companies with no CAMs (only 2% are now), we’ll likely continue to see more CAMs in a more complex world.

(Data furnished by Audit Analytics)

I may not have a crystal ball to predict the future of CAMs, but I believe that the better we get at analyzing critical audit matters at a granular level, the better we become at identifying those matters that will make the difference to users of financial statements. And that’s a win for all.