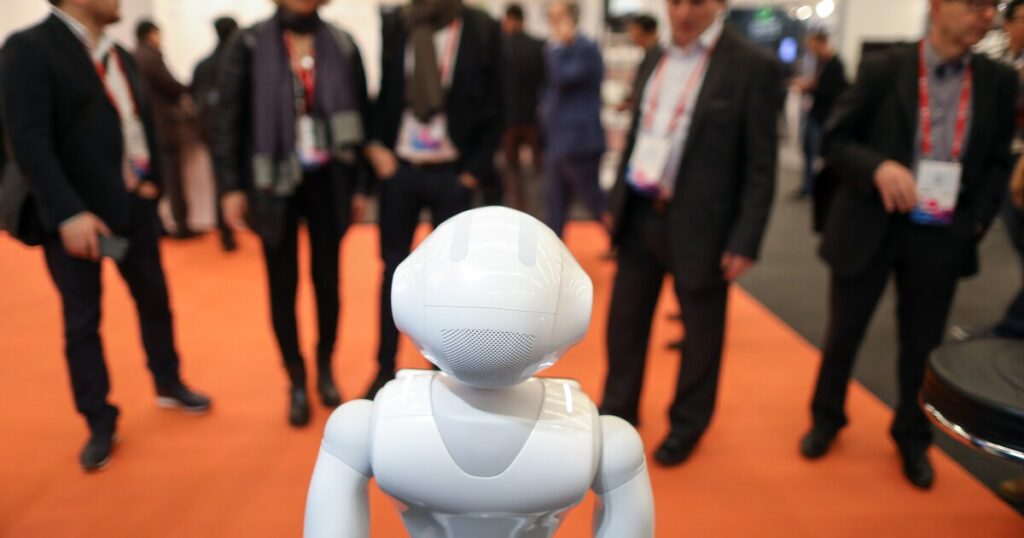

Study recommends small “robot tax”

As machines take on more roles in the economy that used to belong to humans, concerns about their effect on social inequality has begun to rise. However, a small tax on their value may serve to address some of the most disruptive impacts on human workers.

This is according to a recent study from Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Specifically, the study finds that a tax on robots should range from 1% to 3.7% of their value.

To determine this number, researchers used several empirical studies on the relationship between robots and wage and employment disruption to build a statistical model. This was used to evaluate a few different scenarios, and included levers like income taxes as other means of addressing income inequality.

They then applied this model to wage distribution data across all five income quintiles in the U.S. Where data indicated that technology has changed wage distribution in one of these quintiles, the magnitude of that change was used to produce an optimal tax estimate. By using the overall wage numbers, they can avoid making a model with too many assumptions about, say, the exact role automation might play in a workplace.

The researchers noted that 1% to 3.7% is quite a low number, indicating that only modest tax policies would be needed to manage disruption. They also said that this suggested tax could get lower over time, as their research found that the disruptive effect of robots starts leveling off the more there are in the economy.

The researchers also applied the model to international trade, which said that the optimal tax on imported goods should be between 0.03% and 0.11%, given current U.S. income taxes.

“Our finding suggests that taxes on either robots or imported goods should be pretty small,” said Arnaud Costinot, an MIT economist, and co-author of a published paper detailing the findings, in a statement. “Although robots have an effect on income inequality … they still lead to optimal taxes that are modest.”

The researchers said that, unlike other studies, they were not coming in with an assumption of whether or not taxes on robots and trade were merited. Rather, they applied a “sufficient statistic” approach, examining empirical evidence on the subject.

“We came in to this not knowing what would happen,” says Iván Werning, an MIT economist and the other co-author of the study. “We had all the potential ingredients for this to be a big tax, so that by stopping technology or trade you would have less inequality, but … for now, we find a tax in the one-digit range, and for trade, even smaller taxes.”