Key takeaways from Trump’s tax returns

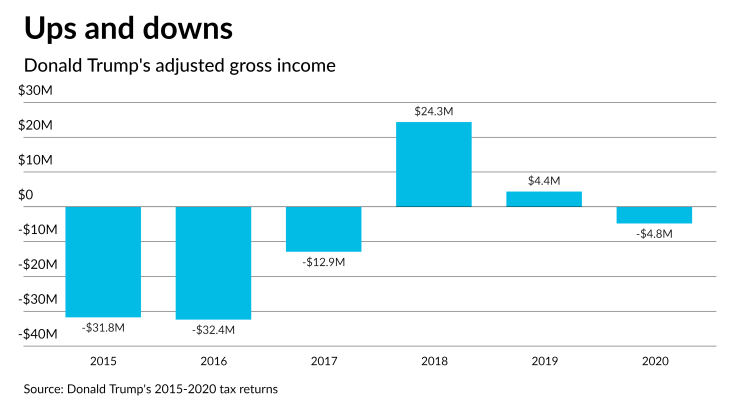

Massive losses and large tax deductions in Donald Trump’s returns reveal how the former president was able to use the Tax Code to minimize his income tax payments.

Democrats on the House Ways and Means Committee released Trump’s tax returns Friday, after he lost a multi-year legal battle to keep them private. The documents show the president’s complex, and sometimes unusual, financial situation. (For more, read “Democrats release Trump’s tax returns.“)

The records illustrate how Trump, as a business owner and a real estate developer, is eligible for a bevy of tax breaks that most taxpayers can’t claim. The filings, which cover 2015 to 2020, also detail how Trump was affected by the 2017 tax cut bill he signed into law.

The documents further show the sheer complexity of the Tax Code. As for many U.S. business owners, the filings span hundreds of pages to account for domestic and foreign assets, credits, deductions, depreciation, and more.

Here are some of the key takeaways from six years of Trump’s tax returns:

$0 tax payment

Trump paid no federal income taxes in 2020, reporting losses at dozens of properties and holding companies. The pandemic almost certainly played a role. An Irish golf resort owned by the former president previously reported a 69% plunge in revenue in 2020.

Nonetheless, some properties still made money. Losses of $65.9 million at a variety of entities were offset by $54.5 million in gains at others that year, according to the returns.

In 2018, the year Trump had the biggest personal tax bill — $999,466 — he paid an effective rate of 4.1% on his income, well below the top 37% individual rate set in his 2017 law.

Democrats have cited Trump’s low tax bills as a reason to overhaul the Tax Code, but were unable to find agreement on ways to make major changes during the two years they held majorities in both the House and Senate. Republicans gain control of the House next week, meaning that any significant tax law changes are likely to be years off.

Trump’s tax law consequences

Trump’s tax law was a mixed bag for him personally. He was able to benefit from some provisions, including expanded write-offs for businesses expenses boosting his companies and the scaling back of the alternative minimum tax, allowing him to claim more individual deductions.

The AMT was originally designed to capture income for wealthy individuals like Trump who managed to avoid paying taxes because of a series of write-offs, like depreciating real estate that is actually gaining value.

The AMT became politically unpopular over time as more upper-middle class households became subject to it and the additional paperwork and compliance headache that come with it. Republicans pared it back in 2017.

Trump has yet to be able to claim the 20% pass-through tax deduction his 2017 tax cut law created for partnerships, LLCs and other small businesses. Trump reported negative business income, also known as losses, from 2018 to 2020, making him ineligible for one of the centerpieces of his signature legislation.

That tax break is scheduled to expire at the end of 2025.

State and local tax limit

Trump’s returns also reflect the $10,000 cap he and Republicans enacted in their 2017 tax law on the state and local tax deduction, negating millions he otherwise could have claimed each year from state and local taxes paid.

For 2019, Trump’s return says he paid $8.4 million in state and local taxes, but could only claim $10,000 under his tax law. The following year was similar: $8.5 million paid but again subject to the $10,000 limitation.

Trump’s $10,000 SALT deduction limitation curbed the tax breaks for many high-income taxpayers, and angered Democrats in high-tax states, including New York and New Jersey. Previously, the deduction was unlimited for some itemizing taxpayers.

Foreign ties

As president, Trump was sued by congressional Democrats and Democratic attorneys general who accused him of violating the U.S. Constitution’s so-called Emoluments Clause, barring presidents from receiving gifts from foreign governments.

The filings do little to clarify the nature and extent of Trump’s overseas financial links, but his 2020 return — from when he was running for re-election and facing questions about his relationship with foreign adversaries — lists several entities that operate in China, including a Shenzhen hotel business.

Sarah Silbiger/Bloomberg

Others of the hundreds of business entities listed also appear to operate abroad, including some in Panama, Brazil and Baku, Azerbaijan.

Charitable gifts

Trump reported giving relatively little to charity while in the White House, including claiming no donations in 2020 at the height of the pandemic.

Trump gave the most while in office in 2017, when he gave nearly $1.9 million in cash. Trump gave about $500,000 in both 2018 and 2019.

Charitable giving was a sensitive subject while Trump was in office. He agreed to shut down his charity, the Trump Foundation, in 2018 after allegations that he was using the entity for his campaign and other personal pursuits.

Audit risk

The non-partisan Congressional Joint Committee on Taxation has noted dozens of potential deductions and other maneuvers that would likely be raised during an audit.

The House Democrats found that the Internal Revenue Service didn’t complete an audit of Trump while he was in office, but the potential red flags raised by the Joint Committee could provide an audit map for the IRS if it pursues an examination.

Tax accountants have also noted that Trump’s use of sole proprietorship entities, which are usually used for small, single-person businesses such as hairdressers or lawn care providers, is also a potential audit trigger for the IRS.