Donor-advised funds taking in more noncash assets like crypto

Donor-advised funds have been receiving more than half of their contributions from complex assets such as shares of public and private companies, real estate and cryptocurrency in the past five years, according to a new report.

The report, released last week by the National Philanthropic Trust, which manages DAFs on behalf of clients, found that people are using noncash assets, including publicly traded securities, real estate, art, jewelry, collectibles and privately held business shares to fund their long-term philanthropic vision and make strategic financial choices.

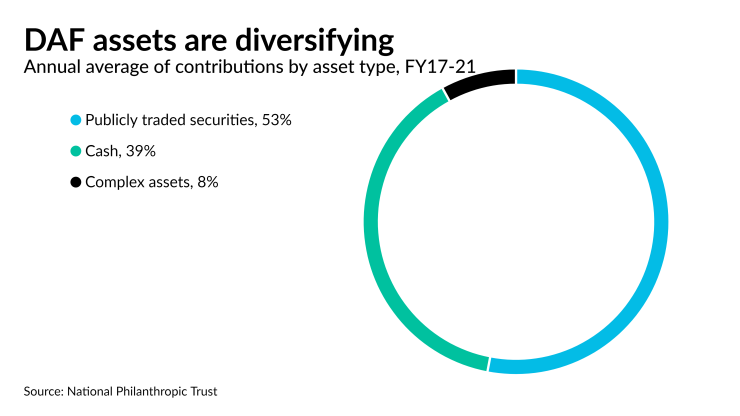

According to the report, 61% of contributions to NPT’s DAFs, on average over the past five years, have been illiquid assets such as shares of privately held businesses, along with stocks, cryptocurrency and real estate. Publicly traded securities made up 53% of DAFs, followed by complex assets at 8% (both of which are illiquid) while cash made up 39% of contributions.

DAFs and private foundations have become an increasingly popular vehicle for charitable giving, especially among wealthy individuals. DAF holders are able to claim charitable deductions, although they have come under pressure from watchdog groups in recent years to pay out contributions faster to charities to meet urgent needs, especially during the pandemic.

“We accept the assets, so they can get whatever deduction they’re entitled to, and then we sell it to get cash in their DAF accounts to allow them to be grantmakers,” said NPT CEO Eileen Heisman. “Sometimes they’re existing donors, so they’ll already have a small, medium or large sum and then we’ll add to it. Sometimes they initiate their DAF with these illiquid assets, and as the market has gone up in the last couple of years as they increase in value — particularly for publicly traded securities, but even with tangible personal property — we’ve seen a great interest in gifting these.”

She sees DAFs as a way to unlock otherwise dormant assets for charitable giving.

“Not everybody considers that,” said Heisman. “It’s often driven by an advisor reading about it or learning about it. When people finally realize that they can do it, and their advisor realizes it, they’re often very happy that they don’t have to part with something that’s in their investments or in cash, that they can part with something that can be an appreciated asset.”

The cryptocurrency market tumbled this year after reaching all-time highs last November, and that has prompted investors to cut back on donations of assets like Bitcoin and Ether.

“Crypto gifts were higher a couple of years ago,” said Heisman. “I don’t think we’ve experienced any crypto gifts recently. People tend to gift tangible personal property or other kinds of assets like this when they’re highly valued. When they’ve dropped in value, the sellers tend to take the loss against their taxes if they’re using this as part of their tax planning. There’s no reason to gift a depreciated asset because you may as well sell it and take the loss. You may want to pick another asset altogether and then depreciate it. People tend to give the appreciated assets to their donor-advised fund and not the depreciated ones.”

The noncash assets can include many other types besides crypto. “In the last five years the average has been greater than 50%, which includes publicly traded securities, but also tangible personal property, and what we call complex assets, such as a personal interest in a business or privately owned stock or sometimes partnerships or other ways in which people hold assets,” said Heisman. “We will occasionally get a gift of private equity or a hedge fund interest. Sometimes those are taxable so we can’t sell them right away.”

NPT needs to make sure before it takes an illiquid asset such as this that it’s able to hold it for a period of time.

“Sometimes we think it’s too long, or if we think there’s a risk to any of these assets, we won’t take them,” said Heisman. “We have a whole due diligence process with a checklist before we accept the asset. There’s a lot of back and forth between the donor and advisor. We probably turn down about 30% of them.”

While a publicly traded security is relatively straightforward to deal with, tangible personal property can involve many more details that NPT has to ask about.

“Every once in a while, we’ll get stock that’s from a director, founder or somebody who’s an owner somehow or has gotten stock during a public event,” said Heisman. “If it’s a publicly traded stock that’s restricted, in that case we either have to get the restrictions lifted or wait until there’s a window to sell it. Sometimes we accept those gifts and other times we decide not to sell them, so we look at each one carefully and distinctly.”

Watchdog backlash

Watchdog groups have argued that DAFs are able to hold such assets for far too long while waiting to sell them, but allowed donors to claim charitable deductions in the meantime on their taxes. Last month, the Institute for Policy Studies released a report that pointed out DAFs have become the fastest-growing recipients of charitable dollars in the U.S. in recent decades. In 2020, for the first time, donations to DAFs were equal to contributions to private foundations, with both receiving roughly $48 billion from donors. The largest single recipient of charitable giving in the U.S. for the past six years has been the Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund, a commercial DAF sponsor, and for the past three years, six of the top 10 charities have been DAF sponsors. The report found that gifts to private foundations and DAFs now divert nearly a third of charitable giving in the U.S.

Giving to private foundations has also increased from 6% to 15% of all charitable giving since 1992, while giving to DAFs has increased from 4% to 15% of all charitable giving since 2007. Together, these charitable intermediaries now take up 30% of all U.S. donations, and have more than quintupled their share of the charitable pie in less than 30 years.

“One thing we’re just seeing is more people opting out of taxes by using the charitable deduction,” said Chuck Collins, director of the Charity Reform Initiative at the Institute for Policy Studies, who co-authored the report. “We want to encourage people to give to qualified charities, but more and more money is getting waylaid into these intermediaries. The implication is a slowing of money flowing to charities, particularly from the wealthy, more money warehoused in intermediaries, more wealthy people using philanthropy as an extension of their power and influence. That actually also changes the recipient projects. Wealthy people give differently than ordinary people. They have different priorities, with more money going to some places and not others.”

He would like to see tax advisors steering their wealthy clients toward giving out charitable contributions sooner rather than later.

“I think the advisors have a huge role in terms of coaching or nudging people on moving money in a more timely way,” said Collins. “Thinking in terms of a legacy orientation might make sense if you’re doing family wealth management, but a legacy orientation in philanthropy is problematic.”

The IPS Charity Reform Initiative and the polling firm Ipsos surveyed over 1,000 adults in June and found that a broad bipartisan majority of Americans strongly support reforms that would curtail the warehousing of charitable wealth. Their recommendations include requiring DAFs to make timely distributions to charities as well as curbing public subsidies of perpetual private foundations.

“The polling that we did with Ipsos showed a wider public desire to see money moved in a timely way,” said Collins. “They don’t like the idea that we as taxpayers have to subsidize legacy perpetual charities. Advisors can play a role in the same way a doctor can encourage somebody to plan for a different end of life.”

He pointed to billionaire philanthropists like MacKenzie Scott or Chuck Feeney as providing positive examples of charitable giving.

“There’s a lot of joy in giving while you’re alive, in moving money for urgent needs and not thinking about what your great grandchildren will be doing with the money, moving it today,” said Collins.

He would like to see timely payouts in the funds increasing, perhaps as a requirement. “I’d just say if people can’t voluntarily figure out how to move it in a timely way, that’s where a mandate makes sense, just to keep the money flowing, discouraging warehousing,” said Collins. He pointed to the NPT report showing that nearly two-thirds of donors are using DAFs to transfer complex assets.

“There’s a lot of money being steered to DAFs with a focus on tax consequences,” said Collins. “Basically I would describe it as a design flaw, that you get your tax break here and there’s no further incentive to move the money in a timely way. That is an unintended consequence of the 1969 tax law. That was not the intent of tax law writers in 1969, to create intermediaries that would never have an incentive for money to move to the recipient groups. It’s really great for the investor, but not so good for the charities.”

Heisman disagreed with the claims in the IPS report of donors warehousing their money for overly long periods.

“We don’t find that people sit on them,” she said. “Our experience is that as soon as it’s liquidated, the donors start making grants right away. Our payouts are about 20%, so we don’t find them to be dormant assets at all. We find the donors to be really committed to wanting to support the social sector. I don’t know where they got their data, but we find donors to be really active and engaged.”

Widening range of donors

She pointed out that it’s not only the ultra rich contributing to DAFs.

“For complex assets, it’s the wealthier donors, but for publicly traded securities it’s a whole range of donors,” said Heisman. “You can have people who have modest wealth, or who have accumulated some money, stock or inherited stock from family members. We find people of all different kinds of wealth contributing publicly traded securities and that’s not limited to ultra high net worth at all. You don’t have to be a multimillionaire to do complex assets. People just happen to own things or they invested in something early on that’s not a publicly traded security. In fact we really love the idea of unlocking illiquid assets for charitable giving. We think it makes the pie of giving available even bigger and donors seem to really like it. Think of these assets as otherwise just sitting there dormant and all of a sudden they’re transferred, they become liquid and donors start to make grants. We think it’s a really good advantage to the social sector that we have that kind of money available and that donors are engaged.”

Two years ago, many of the DAF contributors actually wanted their funds to go out faster in response to the urgent needs of the pandemic (see story), but those priorities have been shifting back to traditional charities.

“I think pandemic-related causes may have slowed down a little bit,” said Heisman. “People are going back to the things they were interested in before, the environment clearly, and then in some cases when there’s a politically-driven event, we might see more money going to places like Planned Parenthood or women’s organizations. People will often look for a charitable organization that might mirror a political interest they have. When there’s been a debate in the public arena, we might see more money going into entities like that. They are charities, not political campaigns, but they’re expressing their interest by their charitable gifts relative to something that could be a political topic.”

While the markets have been turbulent this past year amid recession fears, inflation and rising interest rates, DAFs are continuing to draw contributions over the long term.

“If you think about the market in the last few years, not the last 10 months, the market hasn’t been great,” said Heisman. “But if you think about the previous five years before that when the market went up tremendously, people saw the value in their investable assets and realized that they could give part of them and that’s what they decided to do. It’s also driven by their financial advisor, their accountant, or banker or whoever they use.”