Diversity efforts falling short in accounting and finance

The accounting and finance profession is having trouble retaining employees from different racial, ethnic and gender backgrounds, but there are some strategies organizations can use to hold onto diverse employees.

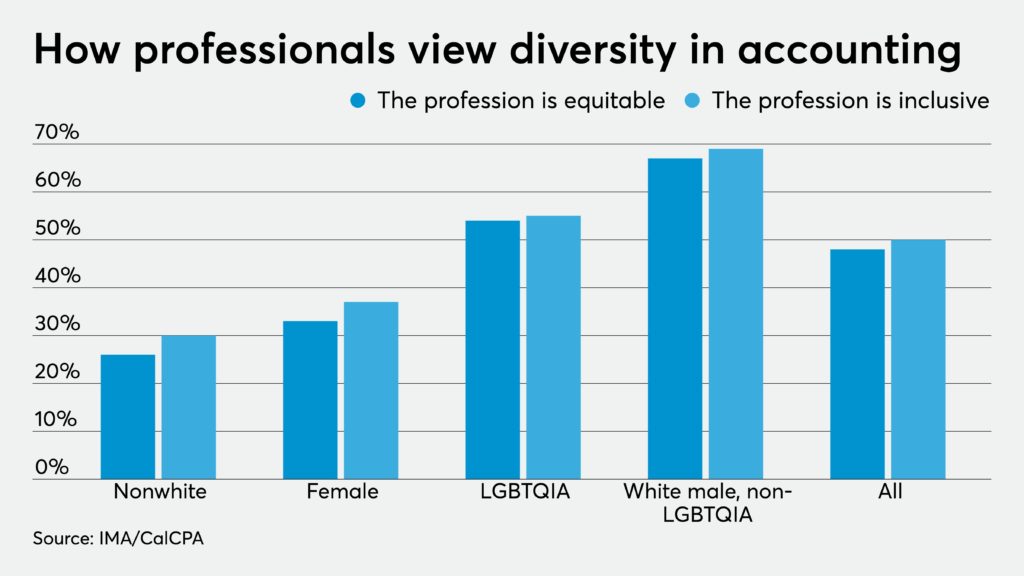

A study released in February by the Institute of Management Accountants and the California Society of CPAs found that 43 to 55% of female, nonwhite, Hispanic, Latino and LGBTQIA respondents have left a company due to a perceived lack of equitable treatment (see story). At least 30% of the respondents from each of these groups have left companies due to a lack of inclusion.

The accounting profession has long been trying to make strides in demonstrating greater diversity at accounting firms and corporate accounting departments, but despite various initiatives at the IMA, CalCPA, the American Institute of CPAs and other groups, the proportion of minority accountants in high-level positions at firms and companies remains relatively low. Nearly one out of five LGBTQIA respondents and nearly one out of 10 female and racially or ethnically diverse respondents reported that inequitable and exclusive experiences contributed to them leaving the profession, according to the IMA and CalCPA study.

“What the IMA research has found is that especially racial minority populations and LGBTQIA people in particular are much more likely to leave the accounting and finance profession because of the lack of diversity, and even more so a lack of inclusion that seems to be in the accounting and finance profession today,” said Derek Fuzzell, chair of the Diversity and Inclusion Committee at the IMA, and chief financial and strategy officer at PAHO/WHO Federal Credit Union in Washington, D.C. “From the perspective of a finance leader, I sit in a CFO role myself, and finding quality talent today is not easy. There are competitive forces out there, but it’s also about finding people who have the right skill set to be a business partner, not just someone who can be a bookkeeper and reconcile accounts. As a profession, by not promoting inclusive practices or equitable practices, we essentially are limiting ourselves in who we can employ in the future.”

He sees the accounting and finance profession losing talent to other industries like engineering and information technology. The problems go beyond recruitment and retention.

“Both attracting and retaining are part of the problem, and the other piece is engaging the current employees,” said Fuzzell. “It’s not just about retaining talent, but about engaging the talent that is there today. We as professionals have to show that the accounting and finance profession is open to everyone.”

He related the story of a lifelong friend who felt that the accounting profession was unwelcoming. “He always told me that he never felt like accounting and finance was open to him because he was an African American individual. When he looked around, he didn’t see people who looked like him,” said Fuzzell. “Whenever he would go to career fairs or wherever there would be somebody who came into our high school or later in college, wherever there were speakers talking about their jobs, they never looked like him, not in accounting and finance. He ended up going into mass communications and works in journalism today, and it’s because the people who showed up to talk to the journalism students looked like him. They represented his demographics, and he felt that it was a lot more open profession. While he may not make as much money — and he and I have had that conversation time and time again — it’s not always just about money. He just didn’t feel like accounting and finance would be welcoming to him as an individual.”

Employee engagement is a key way to retain workers of diverse backgrounds. “One of the reasons why employees tend to turn over is they don’t feel as engaged in the work that they do,” said Guzman. “One of the biggest things we can do as leaders in the accounting and finance space is make sure we have outlets for our employees to be heard because they can share their ideas. They can share their feedback. While this sounds really simple and basic, oftentimes we as leaders have biases that are standing in our way. We may say this is just a bookkeeper who is coming to me or an accounting specialist or an accountant. If they were a senior manager, I might give them more stock. But the reality is that bias sometimes prevents that employee from opening up and engaging, especially if there are systemic issues that are ahead of that person, such as their race or their gender or their sexual orientation or gender identity. They may already not be willing to open up, to share their feedback, to share their thoughts as openly. What we need to do as managers is be much more proactive, go to them and engage with them to pull that kind of information. Let them know we’re there to support them. We have to do that as good finance and accounting leaders.”

One of the main reasons why people leave their jobs is they don’t feel respected by their supervisor. “If we had bosses who were a little bit more inclusive or in tune with the needs of their employees, if they were able to understand and connect with their employees, we might see less turnover,” said Fuzzell. “Instead of having to pay for costly recruiting and training, I’d rather just keep the people I have and develop them and really give them the opportunity to shine.”

Companies need to take a close look at why they’re losing employees, and they may discover that bias is at the root of it. At a previous organization where Fuzzell worked, executives noticed it had high turnover in one of its departments.

“As we started to dive into it, we discovered that white employees on average were likely to stay about five years,” he said. “However, Black and Hispanic employees had an average tenure in that department of less than two years. We wanted to identify the root cause of this. We looked at the manager of the department, who happened to be Black. We had to question him, but it couldn’t be this. But as we started to dive into the data a little bit deeper and really asked probing questions, looking at engagement surveys, talking with people, measuring the side effects, we actually determined it wasn’t the manager at all. It was the assistant manager in the department. The assistant manager had created a very unsafe environment for a lot of the Black and Hispanic employees in that department. They didn’t want to stay after experiencing that within this organization, and they assumed the rest of the organization was the same way. They wanted nothing to do with the rest of the organization.”

The Black and Hispanic employees felt they were being treated unfairly by the assistant manager. “Part of it was microaggressions, the way he would say something or do something,” said Fuzzell. “But the other part of the problem was that employees did not perceive that they were given a fair shake. If there were a training opportunity coming up, he’d almost always favor people who looked like him, specifically white males. Whenever there were opportunities for big projects in particular, he would try to justify to African Americans in the department to say that you really don’t want the risk on this because if it blows up, it’s going to look really bad. So these high-risk and high-reward projects were often given to white males because he didn’t want the egg on his face if the project were to blow up. If a white male failed, that was OK. But if a Black male or a Black female were to fail at that same project, would he have set them up to fail? Would that be the question that would be asked?”

Companies that want to ensure greater diversity in their ranks need to go beyond annual training sessions. “Annual trainings are good for reminders, but they’re not always good for instilling into people the reason why something needs to be done,” said Fuzzell.

Diversity, equity and inclusion programs should be set up in a way where progress can be measured. “There has to be a lot of thought given to how you structure programs to really make them effective,” said Fuzzell. “As an accountant, I love my measurements. I think that in all things you need to set up a baseline. If it’s around diversity in particular, you should have a baseline of where we are, where we’re trying to go, and what progress we’re making. But I think the more important measurements really are around inclusion and equity. Some of the things you can do around equity is to check payouts and promotions. How often is it that a African American or a woman or a homosexual within your organization is actually getting promoted? What is the pay disparity, if any, between women or cisgender or transgender individuals in your organization? You can really start to dive into those kinds of nuances to really figure out whether or not you’re being equitable.”

On the inclusion side, an important indicator is retention level. “If you have engagement surveys, really dive into them,” said Fuzzell. “Figure out what they’re telling you. On retention, the numbers should not just be retention within the organization as a whole, but we should dive in to look specifically department by department. We should be asking tough questions. Are we retaining non-college graduates as well as college graduates? It’s not just in the accounting and finance department, but it really benefits the whole organization to do these kinds of exercises.”

Mentorship and sponsorship programs can help organizations, and executives at all levels should be involved, no matter what their background is. “Formalized mentorship and sponsorship programs can help to bridge the gap,” said Fuzzell. “It’s about having the right sponsor at the right time. As much as we would like to say, ‘Oh, you, Mr. African American executive, would you go and sponsor other African Americans?’ Many organizations don’t have that African American executive in place. We really have to rely on all the executives stepping in. This has to be a mission of every single executive, not just of the CFO, CEO and HR director. Every single executive has to step in and be willing to mentor and really help to identify and guide those next-level starters for the organization, wherever the talent gap may be. When we talk about sponsorships, one of the biggest things we’ve seen and what research shows is that historically white males in particular often get high-risk, high-reward projects, and they’re able to make their career on that. A sponsor should be there to advocate for people, whether they are a different gender identity or genders, if they are different racial or ethnic makeups, cisgender, heterosexual, homosexual. We should have sponsors in place to help build the best and brightest future of what gaps we’re trying to overcome. They have to advocate for the people they sponsor, their proteges, to actually engage in those high-risk, high-reward projects when appropriate.”

Otherwise, the accounting and finance profession will continue to fall short on diversity, equity and inclusion. “It loops back to the IMA CalCPA research study,” said Fuzzell. “The thing that really surprised me is how many professionals were just making the choice with their feet, especially in the LGBTQIA community. They did not feel that the accounting and finance profession was welcoming enough. People were choosing to change companies or, in the worst case, they were choosing to move out of the profession entirely. It’s not only the diversity that’s in front of us. You may or may not know if your employees are heterosexual or homosexual. You may not know what their gender identity is. However, we have to bridge this gap, and it’s not just about the visible diversity we see. It’s also about the invisible, the intangible aspects of diversity. That could be socioeconomic status, upbringing or any other aspect that might be underlying the surface. The best way to do that is just to get to know our employees, try to engage with them in the best way possible, and seek to build their career honestly, openly and effectively. That requires clear and concise communication every step of the way.”